Fireman survivor's own story

Much has been written – in fact and fiction – of the loss of the Titanic, 56 years ago.

Now – posthumously – comes the story of the death-throes of the "unsinkable" wonder ship of her day from the pen of a crew-member survivor.

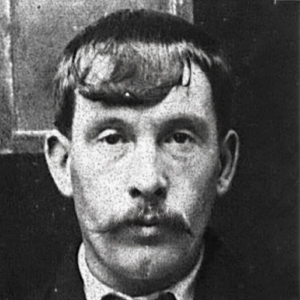

Just before his death – reported in the "Echo" recently – 80-year-old Jack Podesta of Curzan Court, Lordswood, Southampton, fireman in the doomed liner, completed his graphic account of the White Star liner's first and last voyage and of some of his shipmates who "missed the boat".

Dramatically, Mr. Podesta wrote: "So, the crash came – it sounded like tearing a strip off a piece of calico – nothing more, only a quiver."

But that "quiver" marked the beginning of the end.

Fifteen-hundred souls were lost – and he was one of 167 survivors.

At Southampton, after eight o'clock muster on April 10, 1912, which took about an hour, he went ashore again with several other firemen and trimmers for a drink.

"With me and my mate were three brothers named Slade (Bertram, Tom and Alfred). We were at the top of the main road and a passenger train was approaching us from another part of the docks. I heard the Slades say, 'Oh, let the train go by,' but Nutbean and myself crossed over and managed to board the liner.

"Being a rather long train by the time it passed the Slades were too late – the gangway was down – leaving them behind.

"The liner was pulled out of her berth soon after 12 o'clock, towards what we call 'the swinging ground' off the dockhead. It was still on deck and heard the telegraphs ring to start up engines. In Berth 38, off the dockhead, there were two liners moored abreast of each other.

Near collision

"While the Titanic's engines were in motion, the ropes of the two ships snapped like cotton and they drifted away from the wall. That is a thing I never saw before – or after (and I kept sea-going until 1923 when I packed up altogether and worked ashore)."

Mr. Podesta had already seen eight years' sea service before sailing in the Titanic.

The incident at sailing which Mr. Podesta describes is illustrated in the top of page picture.

On April 11 the ship arrived off Queenstown, where all the outward bound White Star ships and Cunard liners called to pick up mails and passengers by tender.

"It was the custom for we firemen and trimmers to go up on deck and carry the mails from the tender to the mailroom. A fireman whom I knew very well (John Coffee) – I was in the Oceanic and Adriatic with him – said to me, 'Jack, I'm going down to this tender to see my mother.' He asked me if anyone was looking and I said 'No' and bid him good luck! A few seconds later he was gone."

Rats leaving

Jack Podesta recalled that everything went well until the Saturday when one of the firemen was taken ill in the stokehold. "He could not tell us what was the matter; he just lost all energy and strength. We got him to his bunk.

"On this very same morning, my chum and I had just gone across firing our boilers and we were standing against a watertight door – just talking – when all of a sudden, on looking through the forward end on her starboard side, we saw about six or maybe seven rats running towards us. They passed by our feet: in fact, we both kicked out at them and they ran aft somewhere.

"They must have come from the bow end, about where the crash came later. We did not take much notice at the time because we see rats on most ships, but I think it is true that they can smell danger.

"Well now came Sunday morning watch and we did our hours; everything was going well all day. The evening watch came and down we went again. In this four-hour watch, we were getting towards the ice – little did we think we were so close.

"Ice ahead"

"We came off at 8 pm and went to the galley for our supper. Some of us passed remarks about the persisting cold. My mate and I put on our 'go ashore' coats and went to the mess room, which was up a flight of stairs, just inside of the whale deck. We finished our meal and coming from the mess room to our living quarters, we heard a man in the crows-nest shout 'Ice ahead, sir.'

"Nutbean and I went on deck and looked around but saw nothing. It was a lovely calm night but pitch black."

Jack Podesta and his friend went back below decks and stayed up talking for an hour or more before turning in.

"We laid in our bunks for about five minutes – several times the man in the crows-nest shouted 'Ice ahead, sir' – nothing was done from the bridge to slow down or alter course. So, the crash came – it sounded like tearing a strip off a piece of calico – nothing more, only a quiver. It did not even wake up those who were in a good sleep.

"The few of us who were awake, went out of our room to the spiral ladder of No. 1 hatch. We saw some men running up from the 12 to 4 room which was on the starboard side (about where the ship struck the iceberg). They must have been flooded out as we could hear water rushing into the forward hold.

"Thought it joke"

"Going back to our room, we began shaking one or two men up from their bunks (one in particular named Gus Stanbrook). I said, 'Come on Gus, get a lifebelt and go to your boat, she's sinking.' He began laughing and simplyu lay back again, thinking it was a joke."

The Titanic was considered virtually unsinkable, mainly because her double-bottomed hull had 16 compartments, four of which could be flooded without endangering the ship's buoyancy.

The 46,000-ton liner was steaming at 22 knots, too fast for the icy conditions, when she collided with the iceberg, ripping a 300ft. gash in her left side. The iceberg ruptured five of her watertight compartments, one more than the safety margin, causing her to sink. She went down at 2:20 am.

"Tore bottom out"

Mr. Podesta's account continues: "She must have torn her bottom at least a quarter of her length. After shaking up some of our watch-mates, we went on deck and saw about ten tons of ice on the starboard whale deck.

"Upon returning to our room again, we began shaking the men up with no avail. Blann came down from the deck shouting 'Look what I found on the deck.' In his hands he had a lump of ice. Then the bo'sun came to our door (his name was Nichols) and shouted 'Get your lifebelts and man your boats.' I knew this was going to happen.

"He was very pale and his lips were in a twitter. He had several ABs with him. I heard he was on his way to the forepeak to get a gangplank as they thought the Olympic was going to reach us."

Jack Podesta and Nutbean followed the bo'sun's orders, but found the boat they were allotted was already full, and they were ordered to help lower it.

Left alone, Nutbean started to walk towards the bridge, while Mr. Podesta groped around, looking for something to make a raft. Nutbean discovered another lifeboat under the bridge and the Chief Officer, Mr. Murdock, told them to jump in.

In the boats

"There were about three able seamen in the boat and we two firemen – the rest were passengers, including women and children, 72 in all. So we took hold of the rope falls and lowered ourselves into the water. Murdock shouted over the side, 'Keep handy, in case you have to come back.' He must have thought her water-tight doors were going to keep her afloat.

"I should imagine we were about five or six-hundred yards away from the ship, watching her settling down – she was going down at the head all the time. But there was once when she seemed to hang in the same place for a long time, so naturally we thought the water-tight doors would hold her.

"Then, all of a sudden, she swerved and her bow went under her stern rose up in the air. Out went her lights and the rumbling noise was terrible. It must have been her boilers and engines as well as her bulkheads, all giving way. Then she disappeared altogether. This was gollowed by the groans and screams of the poor souls in the water.

Two hours to sink

"Soon, it was all silent. I think the ship was about two hours sinking and we were drifting in the boats until dawn. We could see small black objects – bodies and ice floating around, and later, we saw some more lifeboats a good distance away. They were burning some things as signals to one another. Some passengers in our boat burned handkerchiefs or anything as well."

In the early hours they saw the lights of the Carpathia steaming gradually towards them. With the dawn they saw the Carpathia was still some distance away, so they began to pull towards her. It took them until 10 or 11 am to reach her.

After they were picked up Jack Podesta saw two other firemen who had been picked up off a raft, shivering terribly with cold.

"My mate and I gave them blankets and rubbed their legs to start up their circulations. Their names were John Connor and Wally Hurst. Connor died some years ago, but Hurst is still living – he still suffers with his legs every winter. He is 82 years old now."

In fact, Wally Hurst died in December, 1964. This part of Mr. Podesta's account was written shortly before that. Although Hurst was saved, his father-in-law, Mr. William Mintram, was lost.

"Sold for a dollar"

The Carpathia docked in New York on April 18 and the survivors were transferred to the Lapland until the following day. They were taken to the Seamen's Mission where "tea and eats" were laid out.

"I remember an old lady about 70 who was sitting in there. She wanted my belt as a souvenir and I let her have it. In return, she gave me a dollar."

They sailed for Plymouth on April 21 and arrived the following Sunday, when they took the train to Southampton.

"After that we got our voyage pay – single men got £3 and married £5 out of the union funds."

Curator's note: This article was transcribed from images of the original newspaper article taken by Paul Lee. Those images can be accessed on his website.

Source Reference

Title

Last Minutes of Doomed Titanic

Survivor

Alfred John Alexander PodestaDate

May 27, 1968

Newspaper

Southern Evening Echo

Author

Jasmine Profit

Copyright Status

Educational Use OnlyTitanic Archive is making this item available for purposes of preservation and use in private study, scholarship, or research as outlined in Title 17, § 108 of the U.S. Copyright Code. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).