Hettinger Titanic Survivor Recalls 1912 Drama

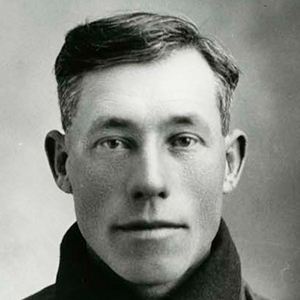

Ole Abelseth was one of approximately 735 passengers out of 2,200 who lived through the disaster and knew what really happened that night.

Abelseth, a hardy Norwegian, lives in the southwestern North Dakota town of Hettinger. Located 38 miles southwest in Perkins County, South Dakota, is the farm he homesteaded in 1908.

He is 86 years old and spends much of his time visiting the folks on Hettinger's main street. He lives in an apartment and his wife is a resident at the nursing home. He doesn't talk much about the sinking of the Titanic which has made him a celebrity. He made it clear that he never liked publicity just because he was a passenger on the ill-fated Titanic. But he agreed to tell his story.

Abelseth was born June 10, 1886, in Aalesund, Norway, where he was reared. In April 1903, at the age of 16, he came to the United States on a small ship. He traveled to North Dakota and settled at Hatton, located northwest of Fargo, where he worked on farms.

In May 1908 he moved to Perkins County, where he homesteaded. He "proved up" his homestead in January 1910. Abelseth noted times were hard, so he took jobs working for ranchers. He worked on a ranch around Columbus, Mont., until the spring of 1910 when he returned to Perkins County to shear sheep.

In the fall of 1910 Abelseth decided to return to Norway because the economic situation in the Dakotas was still tight. He took a steamship from New York back to Europe.

For the next two years he lived with his family in Norway. Early in 1912 several of his relatives expressed an interest in going to the United States to live. These included his 25-year-old brother-in-law, a 20-year-old cousin and two neighbor girls.

Abelseth was persuaded to join them and they booked passage on the Titanic.

They began their journey by crossing the North Sea in a small ship from Bergan to Liverpool. They took a train from Liverpool to Southampton where they boarded the Titanic.

"It was a beautiful ship," according to Abelseth. "It was built in Belfast, Ireland, and took two years to build. It had three separate places to dance, a place to play the piano and a bar."

"It was a double-bottomed boat and the hull was divided into 16 watertight compartments – eight on each side. The ship was 882 1/2 feet long and 92 feet wide. It was supposed to be built for safety, they tried to make it as safe as possible."

According to a story which Abelseth heard, several people from England had gone to Belfast to see the Titanic before she was completed. One person remarked, "This ship must be pretty safe."

Another answered, "It is so safe that even God couldn't sink it."

"Because the ship was supposed to be so safe, there were only 16 lifeboats on board – eight on each side. They could each hold 65 people if the weather was nice."

According to Abelseth, there were also four collapsible boats on the Titanic. These boats had wooden bottoms and canvas tops – thus the name collapsible.

"On April [10], about 11 a.m., all the luggage had been loaded and the passengers were taken aboard."

The Titanic ran into trouble even before it left the dock, according to Abelseth. The Titanic was so heavy that tugboats were employed to pull the ship from the dock so she could be on her way. The tugboats couldn't move her much because of her immense size.

To alleviate the problem one of the propellors on the ship was started. The fast displacement of the large volume of water in the limited area, set up a powerful suction which caused another ship, the "New York," to break its mooring lines.

The result was a near collision – the propellor on the Titanic was immediately stopped and the collision was avoided by a matter of inches.

From Southampton the Titanic crossed the English Channel to Cherbourg, France, where more passengers boarded. The last stop for the Titanic was Queenstown, Ireland, where the last passengers were taken aboard. From there the Titanic headed for New York.

Abelseth said the Titanic was trying to break the speed record on its maiden voyage. It normally took six or seven days to cross the Atlantic, but the Titanic's crew and officials of the White Star Line, which owned the Titanic, hoped to make the trip in five days. So the ship took the northern, shortest, route to New York. The ship's top speed was 28 knots and maintained an average speed of approximately 25 knots, he said.

Abelseth recalls a large number of socially prominent people on the Titanic, including John Jacob Astor, rumored to be one of the richest men in the world. He was about 52 years old and had a young wife about 19 or 20 years old. Astor didn't survive the disaster. However, Abelseth remembers seeing Mrs. Astor on the rescue ship, the Carpathia, after all the survivors had been picked up from the lifeboat.

Isidor Straus, who owned a large department store in New York City in partnership with R.H. Macy, drowned in the accident. After Abelseth reached New York following the rescue, he recalls going into the large department store and becoming amazed at how large it was and the number of people who were employed there.

Also on board were Maj. Archibald Butt, military aid to President William Howard Taft, and Herbert Chaffee, whom Abelseth recalled was from North Dakota and was extremely wealthy. He noted the town, Chaffee, located in eastern North Dakota was named after that family.

On the night the Titanic hit the iceberg it was rumored a passenger remarked to J. Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, that the ship was going quite fast. Abelseth said that most people were aware of the warnings the Titanic had received concerning icebergs in the area.

Ismay remarked, "We'll just speed up more and go by the icebergs."

On the fourth day out, April 14, a Sunday, the weather was nice. The forenoon was quiet – church services were held and dinner was served.

Abelseth said, "You couldn't have seen an ocean more calm."

About 3 p.m. people started dancing and having fun. "Everyone was really enjoying themselves. Some of the crew members joined the fun, but I never saw any of them drunk."

The dancing and merry-making continued on into the night. About 10 p.m., Abelseth told his companions he was going to bed. His room was No. 63 in Compartment G, which was located in the front part of the ship, starboard side. He shared his room was Adolf Humblin, an acquaintance from Norway. Abelseth's brother-in-law and cousin shared a room nearby.

About five or 10 minutes after midnight, Abelseth was awakened by a noise. Humblin asked what the noise was and Abelseth replied that he didn't know. He noted they didn't notice a jar or jolt as would have been expected. There was an interruption in the constant hum of the engines and then they stopped completely.

Abelseth said that lookout Frederick Fleet was in the crow's nest that night. There had been warnings from other ships in the area that there were icebergs in the area. But no one paid much attention to them.

Fleet didn't have binoculars, but he spotted something ahead. It was still too far ahead to determine was it was. He called the bridge and said he had spotted something. When the ship drew closer to the object, Fleet saw that it was a large iceberg. He once again called the bridge and said he saw an iceberg straight ahead.

The crew men running the ship's engines were told to put the portside engines in reverse to turn the ship and hopefully avoid the collision.

Abelseth noted since it took three miles to turn the Titanic half way around and five miles to completely turn the ship, it was impossible to avoid hitting the iceberg.

The iceberg struck the ship back of the bow on the starboard side. The iceberg followed the ship on the side and ripped open the water tight compartments.

Abelseth surmised that if the ship's crew had made no attempt to turn the ship it would have struck the iceberg head-on and smashed in the hull, but the boat wouldn't have sunk because the watertight compartments wouldn't have been ripped open.

Upon hearing the unusual noise, Abelseth told his roommate he would go up on deck and see what had happened. Abelseth noted the Titanic had several decks. When he reached the boat deck he saw a few sailors standing around, not at all alarmed, and a few pieces of ice. He asked them if there was any danger and they said there was nothing wrong and that he should go back to his room. After he left the deck he heard the doors being locked that led to the deck.

Abelseth didn't believe the sailors so he got his relatives up and they walked the entire length of the ship to the section of the ship where the young ladies were staying. He was concerned about the two young Norwegian girls because he had promised their fathers that he would look after them until they got to the United States.

When they reached that section of the boat, the girls were already up. Abelseth told them to get their life preservers on.

They then walked to the poop deck, which is a partial deck. "There were many people on the deck by then...Some took the whole thing as a joke, and others were crying. Many people gathered together their belongings and were carrying suitcases, bundles and blankets."

The steerage or third-class passengers couldn't get to the boat deck because the doors leading there were locked, but they could look up and see the scene there.

Abelseth remembers that there were rockets being fired from the ship to alert other ships of Titanic's distress.

The people on the poop deck saw the boats being loaded. But the sailors were having a hard time getting the lifeboats launched properly and it took a long time for each boat to be launched.

Abelseth said one lady on the Titanic had gone to a fortune teller before her journey and was told that she would die on water. Ironically she decided to stay on the Titanic because she thought if she went on the lifeboats it would certainly mean death.

After most of the lifeboats had been set out, a sailor came and opened the door and took the girls and ladies on the poop deck up to the remaining lifeboats and put them in.

By the time the men steerage passengers had reached the boat deck all the lifeboats had been set out and they were rowing quickly away from the Titanic. They thought the suction of the ship's sinking would pull them under or else the people that were thrust into the water would try to get into the lifeboats and capsize them.

After the lifeboats were all gone, the crewmen told the passengers, "It's everyone for themselves, everyone has a free chance to save themselves."

Abelseth said most of the passengers on the boat deck made a dash to the front of the ship where the collapsible boats were kept.

Abelseth suggested to his brother-in-law and cousin that they not get into the mad rush of hundreds of people. So they stood by one of the boat davits on the edge of the boat deck. (A davit is a frame that holds lifeboats on the boatdeck of a ship).

"I'll never forget it, people of all classes, rich and poor, and people of all religions were standing on the deck. Some people walked nervously back and forth on the deck. But most people all joined hands and stood there. They all said in unison 'Save us, save us.' It was a solid roar."

"The ship started to list more and more and we were still standing by the boat davit." Abelseth's brother-in-law said, "We better jump off now or the suction will pull us down."

Abelseth replied, "We don't have much chance in that cold water. Let's just stay here a little longer.

"My cousin said we should take a rope and tie us together because he couldn't swim. But I knew that wouldn't work.

"It was really a terrible sight to see, those 1,500 people all crowded together on the deck with the ship listing more and more. And there wasn't anything anyone could do.

"The bow of the ship went down first. As the water went over the boilers, one of the smokestacks fell down. Those smokestacks were so large that two boxcars could fit into one of them."

About the time the smokestack fell, Abelseth decided it was time to get off the ship.

"It was hard to say good-bye to each other because we didn't know what was going to happen. I took hold of a rope that was connected to the david and let myself down the side of the ship into the water."

It was quite a distance to the water because the part of the ship the people were now on was gradually swinging higher and higher into the air.

"When we decided to get off the boat, people were starting to slide off the deck right into the water because they could no longer stand up."

"When I let myself down the side of the ship, that was the last I ever saw of my brother-in-law and cousin, I don't know what they did. When I reached the water. I discovered how cold it really was. I just had on my suit. I left my heavy coat on the deck.

"After I got into the water I tried to swim away from the ship before it sank.

"While in the water someone grabbed me around the neck and tried to get on top of me. I tried to get away but he kept hanging on. When the ship finally sank it caused a motion in the water and that is when I got away from him.

"A minute or so later, another guy grabbed me on the leg but I got away from him easier than the other one.

"I saw one of the collapsible boats in the water a few yards ahead of men so I swam towards it. When the people on the boat saw me they said 'Don't let him on the boat – he'll capsize it.' But I swam up to the side of the boat and got into it without much trouble. There were about 15 people on this boat including one woman.

"That water was so cold some people died within five minutes after they were in it. I thought I would be able to float around in the water for quite a while, but I found I couldn't. If the water hadn't been so cold, a person could probably have floated for hours.

"There was an Irish man on the collapsible boat I met at Southampton. I remember he said 'Won't there be a crowd at the harbor when we get to New York?' We talked a little while more and then I didn't see him again until on the collapsible boat.

"I don't know what his name was, I just called him Bill when I was talking to him on the collapsible boat.

"I said 'Brace up Bill – there's a ship coming to rescue us.' But he didn't respond much, he just said, 'Leave me alone.' Then he died. He never knew what a large crowd there was in New York when the Carpathia sailed into New York with the survivors.

"Another man in the collapsible boat complained of cramps. He was sitting behind me and he put his arms around me. He died that way. I had to take his arms off me.

"All the while we were on the boat the bottom of it was filled with water."

Abelseth noted that the water kept getting into the boat because no one knew how to rig the boat properly.

"Toward morning the wind started to blow and the waves began splashing into the boat. We had to stand in the boat and rock back and forth with the rhythm of the waves to keep the boat steady and keep it from capsizing."

About 8 a.m. the Carpathia, the boat which rescued the survivors, reached the area where the Titanic sank.

Abelseth said the captain of the ship, a Swede named Rostrom, was a very good captain with a great deal of experience at sea.

"He zig-zagged back and forth over the area where the Titanic sank, to make sure he didn't miss any lifeboats. He knew the people in the lifeboats wouldn't think of keeping together. In this way he was able to pick up all the people in the lifeboats."

The collapsible boat which Abelseth was in was the last to be picked up. It was six hours from the time Abelseth climbed onto the collapsible boat until they were picked up. After the survivors were taken aboard the Carpathia they were given coffee and brandy.

There wasn't much room on the Carpathia because it had a full load of passengers and then took on approximately 735 survivors.

After the Carpathia had searched for all the rescue boats and found presumably all of them, a memorial service was held over the spot where the Titanic sank. Then she sailed for New York. Other ships in the area continued to search for rescue ships and picked up the floating bodies. One ship picked up Abelseth's brother-in-law's body.

The first night aboard the Carpathia, Abelseth slept on the floor in his wet clothes and the second night he slept on two chairs pushed together to make a bed.

It took the Carpathia three days to get to New York. Upon their arrival in New York the entire dock was swamped with people.

"There were so many people there – it took many mounted policemen to hold them back."

"When we got off the boat everyone was very nice to us. We were taken to St. Vincent's Hospital in New York City for checkups.

"Someone even cleaned my suit for me because it was all wrinkled and full of salt from the water."

Abelseth stayed in New York for one month to claim his brother-in-law's body. He also gave his testimony about the trip to Sen. Alden Smith of Michigan, who conducted an investigation into the disaster.

The White Star Line gave all the survivors a ticket on the railroad to any destination they wanted. Abelseth got a ticket to Minneapolis. He had lost all his personal belongings, including money.

"It was very hard on me at first. I hated to lose my brother-in-law. I was so restless. I didn't know what I wanted to do. I hired out to ranchers and farmers and took a trip to Canada to settle my nerves."

He eventually returned to his farm in Perkins County and raised grain, cattle and sheep. In 1943 his son took over the farm and Abelseth bought a house in Reeder, 13 miles west of Hettinger. While livin in Reeder he was a hog buyer. In 1946 he sold his house and moved to Tacoma, Wash., where he and his wife lived for 22 years. When his wife became ill they returned to Hettinger.

Recalling some of the controversies that surrounded the disaster, Abelseth said many events that were rumored to have happened on that night were not true.

He never heard the band playing "Nearer My God To Thee." He didn't doubt the band was playing. "I never heard it. But I never was close to where they would have been playing."

Another story told was the officers of the ship committed suicide, which Abelseth dismissed as being false.

There are also stories many of the rich people got into the boats before the women and children.

"That wasn't true. Those rich and prominent men were very noble. They stayed on board with the rest of the men."

Curator's note: This account is excerpted from the full article published in the Adams County Record.

Source Reference

Title

Hettinger Titanic Survivor Recalls 1912 Drama

Survivor

Olaus Jørgensen AbelsethDate

January 24, 1973

Newspaper

Adams County Record (Hettinger, ND)

Author

Shirley Frey

Copyright Status

Educational Use OnlyTitanic Archive is making this item available for purposes of preservation and use in private study, scholarship, or research as outlined in Title 17, § 108 of the U.S. Copyright Code. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).