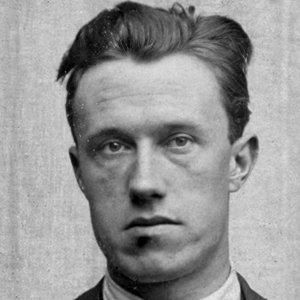

Third-class steward Sidney Daniels (18) and from Hampshire, jumped overboard. He leaped as far as he could, cannon-balled into the water in a sitting position – and he still sucks his breath sharply when he thinks of the stabbing cold on that freezing night in the Atlantic.

Holding on to a lifebuoy which suddenly bobbed up, Sidney looked behind him. The stern of the Titanic was perpendicular in the night sky, all lights blazing as she dived down beneath the waves.

That night has been incessantly dubbed "a night to remember." For Mr. Daniels, now living in Copnor, Portsmouth, it has proved a night impossible to forget.

For years he was unable to talk about the tragedy. "I lost so many shipmates," he says, simply.

Years ago, though, he spotted a picture of the ill-fated ship leaving Belfast Lough, in a local antique shop and bought it on the spot. It now has pride of place in his sitting room which somehow it dominates.

That transaction prompted him to search for his locker key: "Prom Deck F, Locker 43," which he retains as his only visible memento of that cruel night.

Mr. Daniels went down to the sea in ships nearly all his working life, except for World War One service in the trenches.

The Titanic disaster happened less than a year after his first voyage as a plate-washer on the Olympic's maiden voyage. Then young Sidney Daniels was selected to go to Belfast to help bring the brand-new Titanic to Southampton.

"I felt proud to be part of such a wonderful ship. Had I but known what the future held..."

He recalls the maiden voyage in vivid detail.

"We were beating the Olympic's mileage and all went fine until 11:30 on Sunday night. Tired out, I was sleeping in my bunk when, with the rest of my mates in the 'Glory Hole' I was awakened by the night watchman, told to get dressed and muster on the boat deck with our lifebelts.

"My Lifeboat was Number 13!"

"We were none too pleased as we thought it was all just a boat drill for the crew, but when we had orders to swing out the boats and prepare for lowering we realised it was serious.

"I was sent below to fetch the passengers. When I got back I found my boat had been lowered already. After helping to clear a collapsible craft with my pocket knife I walked around to the starboard side where all was quiet.

"Then I walked around towards the bridge and saw the water coming up the companionway pretty quickly. I could feel no motion from the ship but saw she had listed well to port and was down at the head."

It was just about then that Sidney Daniels realised he would have to move sharply if he was to stand any possibility of surviving. By that time the sea was swilling around the deck.

"I held on to a boat davit, ready to jump overboard. And I jumped – into the darkness and swimming away as far as I could. For how long I don't know, but I found a lifebuoy with a man clinging to it.

Suction Fear

"I held on to that for a while, and as I turned back to look I could see the stern of the Titanic standing almost straight up in the air, I knew the suction could drag us down and I suggested to the other man that we moved away.

"He did not answer and away I went. Eventually I saw a capsised lifeboat with several men clinging to it. Standing on this I pulled myself up on the keel and sat there, just out of the water.

"It was the same collapsible boat that my pocket knife had helped to cut clear. I wish I could have kept that knife! It was instrumental in saving 24 lives, including my own."

Even then, Mr. Daniels is convinced he would have died – as another survivor did – but for a passenger who stopped him going to sleep.

"If I had slept, it would have been my last.

"Someone started swearing and cursing for some unknown reason. But I heard another voice say it was not the time for that but, rather, for praying. So we said the Lord's Prayer."

Many nationalities were among the 24 people who sat in the boat all night, impatiently waiting for the dawn. Eventually like almost all the other survivors, they were picked up by the Carpathia.

Days later, the ship steamed into New York with a hero's reception with dozens of smaller ships crowding around in the river, welcome sirens hooting through the air.

Daniels was transferred to the SS Lapland which took him, and other crew members back to Plymouth, England and an indifferent reception.

For once, the Devon port had not had a significant section of its population decimated by a disaster at sea.

It was different at Southampton.

"We arrived at the old West Station, from Plymouth, to find it crowded with anxious people. I would say that the prevailing atmosphere was one of great sadness.

"Some of the people milling about weren't sure whether their relatives were coming back or not – I had been reported missing to my father, for instance."

However, like most tragedies, this was touched with the comic. For Sidney had wired to his father with the terse message: "Arrive safe, Lapland."

And dad took it to mean he had been carted off to the land of Lapland, which he hurriedly looked up on a world atlas.

Still that telegram had arrived on his father's birthday! He says it was the best present he ever had.

"He kept a pub in Albert Road, Southsea. That night, it stayed open rather longer than usual."

But you can't keep a good seaman away from a ship for long, and Sidney was transferred to the Olympic once more, staying with her for all 220 voyages until she went to the breaker's yard in 1936.

His next ship was the stylish Berengaria, on which he sailed until its demise in 1936. Eventually, even Mr. Daniels had to leave the life he loved and instead, worked in Portsmouth dockyard until retirement in 1962.

But the sounds and pictures of that night in 1912 are buried deep in Mr. Daniels' heart.

Curator's note: This article was transcribed from images of the original newspaper article taken by Paul Lee. Those images can be accessed on his website here and here.

Source Reference

Title

Owes his life to knife

Survivor

Sidney Edward DanielsDate

April 4, 1979

Newspaper

Southern Evening Echo

Author

Guy Fleming

Copyright Status

Educational Use OnlyTitanic Archive is making this item available for purposes of preservation and use in private study, scholarship, or research as outlined in Title 17, § 108 of the U.S. Copyright Code. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).